Question 18 Part 1

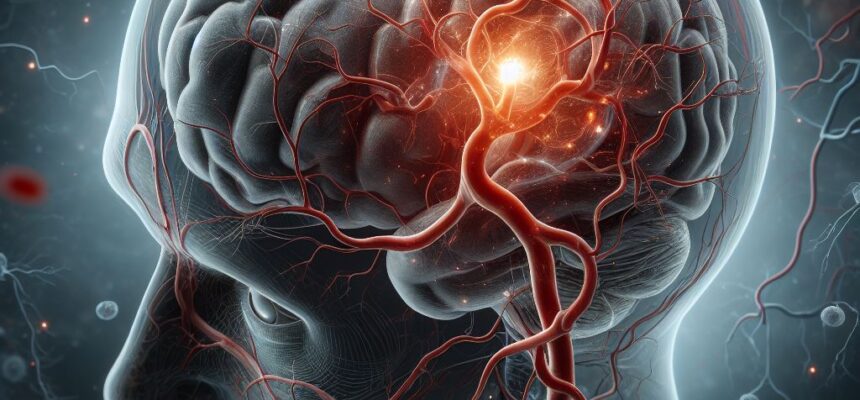

Cerebral Infarction: Etiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Symptoms, Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis.

What is stroke – Types of stroke

A stroke is the abrupt disruption of continuous blood flow to the brain, resulting from either blockage or bleeding. This occurrence leads to damage to the brain tissue and a subsequent loss of function. The interruption of blood flow to cerebral tissue can be attributed to a cerebral infarction, giving rise to the most common stroke type: ischemic stroke (IS), or it can be caused by bleeding in the brain, leading to hemorrhagic stroke (HS), which is considered to have a higher mortality risk compared to IS.

A third type of stroke is a transient ischemic attack (TIA), characterized by a brief blockage of blood flow to the brain that does not cause permanent damage. TIA serves as a warning sign for a potential future stroke and can manifest with stroke-like symptoms, lasting for a few minutes or persisting for up to 24 hours.

Ischemic stroke

This is the most prevalent type of stroke, accounting for approximately 80% of all stroke cases. An ischemic stroke transpires when the blood supply to a section of the brain is impeded or diminished due to blood clots or other particles obstructing the brain’s blood vessels. Consequently, the affected brain tissue is deprived of oxygen and essential nutrients, leading to the initiation of cell death.

The occurrence of ischemia arises when blood vessels undergo narrowing or blockage, resulting in a reduction of blood flow and, consequently, a diminution in oxygen levels—a condition referred to as ischemia.

Pathogenesis of ischemic stroke

Ischemic strokes can be categorized into two primary types: thrombotic strokes and embolic strokes. Thrombotic strokes transpire when a blood clot forms within a blood vessel in the brain. On the other hand, embolic strokes occur when a blood clot, a fragment of plaque, or another obstructive element originates in a different part of the body, traverses through the bloodstream, and becomes lodged in the blood vessels within the brain.

Thrombotic Stroke

Thrombotic strokes occur due to the formation of a blood clot in the arteries that supply blood to the brain. This clotting leads to the cessation of function and subsequent death of brain cells in the affected area. Typically, thrombotic strokes arise from the gradual buildup of plaque inside large arteries that have already been narrowed by atherosclerosis. In response, the body deploys clotting factors to generate a blood clot. When this clot becomes sufficiently large, it can obstruct the artery, causing a reduction in the supply of oxygen and nutrients to the brain. Thrombotic strokes can impact either large or small arteries within the brain.

In the case of large-vessel thrombosis, the blockage occurs in major arteries, significantly affecting a larger portion of the brain and potentially resulting in severe disability. Plaque accumulation typically progresses slowly over time without exhibiting any symptoms until a clot suddenly forms, blocking the artery and manifesting symptoms dependent on its location.

Conversely, small-vessel thrombosis transpires in the smallest and deeper arteries that supply blood to specific areas within the brain. This type of stroke is termed lacunar stroke and often exhibits minimal symptoms, as only a small part of the brain is affected.

Embolic Stroke

Embolic strokes, like thrombotic strokes, result from a blood clot. However, in the case of embolic strokes, the clot forms elsewhere in the body, breaks off, travels through the bloodstream, and ultimately lodges in a brain artery. These strokes typically stem from clots originating in the heart when blood isn’t effectively pumped, leading to clot formation. Atrial fibrillation is a primary contributor to clot formation, while less common causes include carotid artery disease, infections, or heart tumors. Symptoms of embolic strokes closely resemble those of other stroke types and emerge suddenly.

Clinical Symptoms and Warning Signs

As strokes impact various regions of the brain, the manifestation of symptoms is contingent upon the specific area affected.

Middle Cerebral Artery (MCA):

The middle cerebral artery (MCA), the largest branch stemming from the internal carotid artery, is a prevalent site for cerebral occlusion. Symptoms associated with MCA strokes include:

• Hemiplegia (paralysis) on the contralateral side, particularly affecting the lower part of the face, arm, and hand.

• Contralateral sensory loss in corresponding areas.

• Contralateral homonymous hemianopia, characterized by visual field deficits affecting the same half of the visual field in both eyes.

• MCA strokes tend to impact the face and arm more severely than the leg.

• In cases where the stroke affects the left (dominant) brain hemisphere, aphasia may occur, involving partial or total loss of language communication. Since most individuals are left-hemisphere dominant, expect patients with right-sided weakness to exhibit aphasia.

Anterior Cerebral Artery (ACA)

The anterior cerebral artery (ACA), a branch of the internal carotid artery, supplies the anterior medial portions of the frontal and parietal lobes. Symptoms associated with ACA strokes include:

• Contralateral leg weakness and sensory loss.

• Cognitive and behavioral changes.

Posterior Cerebral Artery (PCA)

The posterior cerebral artery (PCA), originating from the top of the basilar artery, nourishes the medial occipital lobe and inferior and medial temporal lobes. PCA distribution commonly results in visual deficits, specifically contralateral homonymous hemianopia.

Vertebrobasilar Strokes:

• Cerebellar strokes often lead to impaired balance and coordination, known as ataxia.

• In brain stem strokes, signs and symptoms vary based on the specific stroke location. Possible manifestations include hemiparesis or quadriplegia, sensory loss affecting half or all four limbs, double vision, slurred speech, impaired swallowing, and decreased level of consciousness. An alternating stroke, in the context of the brainstem, typically refers to a stroke where symptoms manifest on the contralateral (opposite) side of the body from the lesion, and on the ipsilateral (same) side for certain cranial nerve-related symptoms. This term reflects the alternating pattern of motor and sensory pathways in the brainstem.

Other symptoms of stroke can be

• Dizziness or vertigo

• Nausea and vomiting

• Complete paralysis of one side of the body

• Difficulty of swallowing (dysphagia)

• Confusion and trouble speaking or understand speech

• Seizures

• Memory loss

• Headaches (Usually sudden and severe)

• Loss of consciousness

• Coma

Warning Signs

It is imperative for every healthcare provider to promptly recognize stroke symptoms. The BE FAST acronym serves as a helpful tool for rapid stroke evaluation and is widely employed worldwide.

BE FAST:

• B: Balance – Sudden loss of balance or coordination.

• E: Eyes – Sudden vision changes or loss in one or both eyes.

• F: Face – Facial drooping, particularly on one side.

• A: Arms – Sudden weakness or numbness in one or both arms.

• S: Speech – Difficulty speaking or slurred speech.

• T: Time – Time is critical; seek immediate medical attention if any of these signs are observed.

Recognizing these warning signs promptly and taking swift action can significantly improve the chances of positive outcomes for individuals experiencing a stroke.

Diagnosis

Clinical examination remains the cornerstone, as the prompt recognition and response to stroke symptoms significantly influence patient outcomes. The gold standard for imaging diagnosis is a non-contrast CT scan, swiftly identifying areas of infarction. This aids healthcare providers in making informed decisions about treatment and management. It is noteworthy that in the initial hours, a brain CT scan may appear normal with no evident areas of infarction. While this doesn’t exclude an ischemic stroke, it helps eliminate other conditions that can mimic ischemic stroke, such as brain hemorrhage.

Management of the Patient

Time is critical in stroke management. Swift evaluation is imperative, especially as certain treatments, like thrombolytic therapy, are most effective within the first few hours after symptom onset. The concept of “time is brain” underscores the urgency of early intervention to minimize potential damage.

Calculating Stroke Onset

Determining the time of stroke onset is pivotal for treatment decisions. Clinically, the time of stroke onset is defined as the last moment the patient was seen as normal. This information is crucial in establishing eligibility for time-sensitive interventions, emphasizing the BE FAST approach for quick stroke evaluation.

Stroke Severity

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) serves as a systematic and quantitative assessment tool to measure the severity of stroke. This 15-item neurological examination stroke scale evaluates the impact of acute cerebral infarction on various aspects, including consciousness, language, neglect, visual-field loss, extraocular movement, motor strength, ataxia, dysarthria, and sensory loss. A trained observer assesses the patient’s ability to answer questions and perform activities without coaching or making assumptions about the patient’s capabilities. Ratings for each item range from 0 to 5 on a 3- to 5-point scale, with 0 indicating normal function. Untestable items are also accounted for, and the total scores range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating greater severity. This standardized tool comprehensively evaluates neurological functions, guiding treatment decisions based on the total score.

Modified Rankin Scale

The Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) plays a crucial role in assessing the long-term impact of a stroke on a patient’s functional abilities, providing a measurement of the degree of disability. The scale ranges from 0 to 6, with the following interpretations:

0: No symptoms

1: No significant disability

2: Slight disability but able to perform daily activities

3: Moderate disability requiring some help

4: Moderately severe disability, dependent on others

5: Severe disability, bedridden, and requiring constant care

6: Death

Understanding a patient’s Modified Rankin Scale score enables healthcare providers to tailor rehabilitation strategies and support services, thereby enhancing the individual’s quality of life post-stroke. This scale provides valuable insights into the functional impact and overall disability level experienced by the patient in the aftermath of a stroke.

Differential Diagnosis

Distinguishing cerebral infarction from other neurological conditions is crucial for accurate and timely intervention. Various conditions, including transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), intracerebral hemorrhages, and metabolic encephalopathies, can present with symptoms that may overlap with those of a stroke. It is essential to be cognizant of stroke mimics, wherein conditions such as hypoglycemia or epileptic seizures can manifest stroke-like symptoms.

Key considerations in the differential diagnosis process include:

• Onset of Symptoms: Stroke symptoms often manifest more suddenly than those of other conditions. Assessing the abruptness of symptom onset can be indicative.

• Risk Factors: While it is important to inquire about stroke risk factors, it is crucial to recognize that patients without apparent risk factors can still experience strokes. A comprehensive evaluation is necessary.

• Medical History: A thorough medical history review is essential. Assess for non- stroke conditions that can produce neurological effects, such as hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, medication-related effects, sudden drops in blood pressure, and, if applicable, a postictal state following a seizure.

• Neurological Examination: A detailed neurological examination aids in identifying specific signs and symptoms that may point towards a stroke or an alternative diagnosis.

By considering these factors, healthcare providers can effectively navigate the differential diagnosis landscape, ensuring appropriate and targeted management based on the specific condition presenting in the patient.

References

Transient ischemic attack (TIA): Mayo Clinic https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases- conditions/transient-ischemic-attack/symptoms-causes/syc-20355679

Stroke: CDC Enters for Disease. Control and prevention https://www.cdc.gov/stroke/about.htm

Ischemic stroke: Mayo clinic home page https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ stroke/symptoms-causes/syc-20350113

Ischemic stroke: Cleveland Clinic https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/5601-stroke

Ischemic stroke: The Ohio State University https://wexnermedical.osu.edu/brain-spine- neuro/stroke/types

Types of stroke: Johns Hopkins Medicine https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/ conditions-and-diseases/stroke/types-of-stroke

Thrombotic stroke: Tampa General Hospital https://www.tgh.org/institutes-and-services/ conditions/thrombotic-stroke

Thrombotic stroke: Harvard Health Publishing https://www.health.harvard.edu/a_to_z/ thrombotic-stroke-a-to-z

Embolic stroke: Tampa General Hospital https://www.tgh.org/institutes-and-services/ conditions/embolic-stroke

Symptoms – Stroke: NHS https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/stroke/symptoms/

https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/types-of-stroke/ischemic-stroke-clots

Verified by Dr. Petya Stefanova